For many families with children who have rare heart conditions, the fear of worst-case scenarios or life-threatening symptoms is never far away.

But thanks to a groundbreaking cheek swab test being developed at City St George’s, University of London and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), affected children may soon have access to a safer, simpler way to monitor their medical conditions, offering reassurance to families.

Monitoring arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies

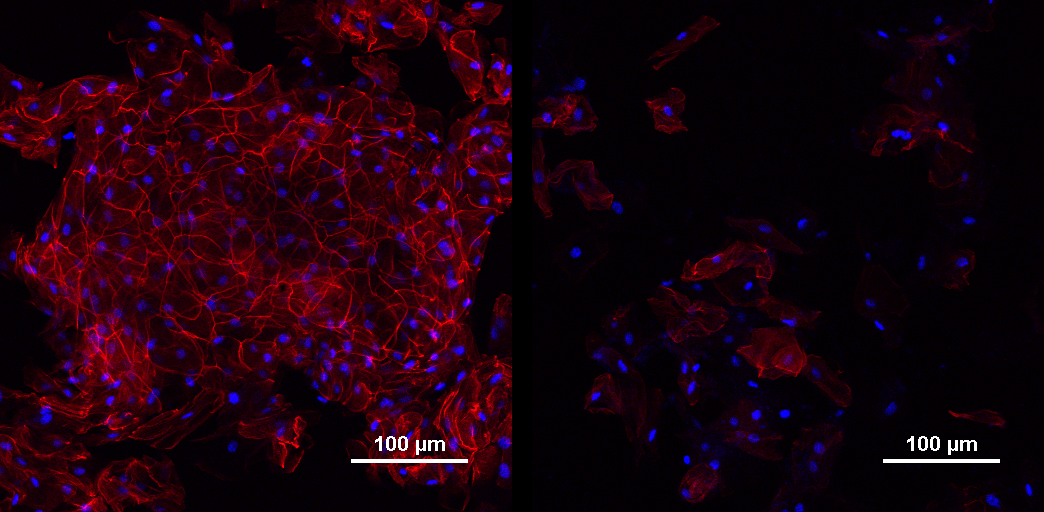

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies (ACM) are genetic conditions that cause the heart muscles to weaken, potentially leading to abnormal rhythms and sudden cardiac death. Current monitoring methods for children with ACM, such as heart scans and blood tests, can miss microscopic changes occurring within the heart. This gap in diagnostics is where the innovative cheek swab test comes in.

Funded by the British Heart Foundation (BHF), the test offers a non-invasive way to track protein changes in cheek cells, which reflect similar changes in heart cells. If successful, it could revolutionise how ACM is managed in hospitals nationwide, reducing the risks of sudden complications for patients.

“Our test is providing a much-needed window into the minute changes happening in the hearts of ACM patients, in a totally risk-free, non-invasive way,” says Dr Angeliki Asimaki, a Senior Lecturer at City St George’s who is leading the study. “Doctors can be warned about which of their patients are most at risk of dangerous heart rhythms and other symptoms, allowing them to tailor treatment. Patients, particularly children, have told us they hugely prefer the speed and ease of the cotton bud cheek swab.”

Bea’s journey with ACM

For 10-year-old Bea, who has ACM, the journey began three years ago when she started experiencing episodes of ventricular tachycardia – a dangerously fast heart rhythm – accompanied by breathlessness and dizziness. Initially, she mistook these symptoms for anxiety, but with a family history of ACM, genetic testing soon confirmed her diagnosis.

“The test is adding another layer of reassurance to the family that the condition is being monitored,” says Bea’s mother, Liz. “We think it’s so important to take part in this research to improve how ACM is monitored and managed for children in the future.”

Bea now has an internal heart rhythm monitor fitted, which alerts her family and doctors at GOSH whenever she experiences a dangerously fast rhythm. This has spared her countless hospital trips for overnight monitoring, allowing her to continue her education and hobbies with minimal disruption.

“We feel it’s really important to not let Bea’s condition get in the way of a normal childhood,” Liz adds. “She stays active by doing swimming and is in a weekly theatre school.”

Reassurance for families

For families like Bea’s who are living with ACM, the unpredictable nature of the condition can be daunting. However, the swab test offers a glimmer of hope, providing quicker results and a deeper understanding of the disease.

“People with ACM often live with day-to-day worries because of the unpredictable nature of their condition,” says Professor Bryan Williams, Chief Scientific and Medical Officer at the BHF. “The simple monitoring test has the potential to provide reassurance to patients and their families that their condition is being kept under a watchful eye by medical professionals.”

The future of ACM care

Besides the current swab test, the researchers are also investigating the potential for monitoring women with ACM during pregnancy – a critical period when heart strain increases. As a result, this research could not only help Bea and those like her, but also other families who are affected by ACM, reducing the risk of sudden complications.